Visual vs Cerebral

/The most common question I get in my email is, “How would you present [insert some new trick that recently came out].”

Today, I’m going to talk about one of my first considerations when thinking about coming up with a presentation. My approach, generally, is to start by asking myself if a trick is visual or cerebral.

Visual - Coins disappear, cards change color, billiard balls multiply

Cerebral - The card they named is at the number they named, the Rubik’s cube they mixed matches mine, I predicted the word they merely thought of.

Of course, to a certain extent, most tricks are on a spectrum. The Rubik’s cube trick certainly has a visual element to it. It’s a trick where you are appreciating the effect with your eyes. But the impossibility of it is really something that takes place in your brain. Metal bending is mostly visual, but not completely so. An implied penetration (where you don’t see the object going through the object) may be right down the middle.

The best way to identify if a trick is purely visual is to ask, “Would this fool a monkey?”

If yes, then you have a primarily visual magic trick.

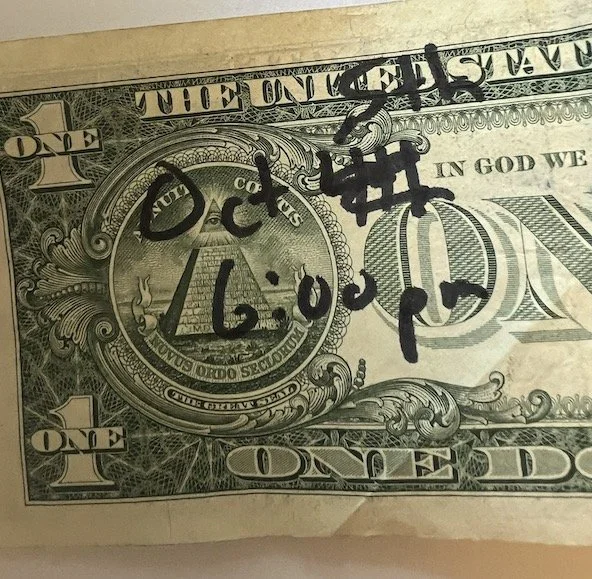

You don’t often have a monkey who is like…

Often, when people are getting into the style of magic I write about here, the mistake I see them make is they take a highly visual piece of magic, and they try to add a cerebral presentation to it. In my experience, it’s hard to make this work.

Visual magic is appealing to a very primitive aspect of our brain. Putting a cerebral presentation on top of it—which is appreciated by a more advanced part of our thinking—doesn’t really go together. It’s like getting a blow job while someone reads you a really good short story. It’s hard to appreciate both simultaneously. And you’re probably just going to be able to concentrate on the more instinctual pleasure.

For the most part, if I have a quick visual trick, I will not burden it with a “deep” presentation. That’s sort of the idea behind the Distracted Artist style. To eliminate the pretense of presentation entirely.

That said, if I do want to add some substance to a quick visual moment, I will do that by “front-loading” the presentation, so I can get it out of the way and the visual moment of magic can be undisturbed. For example, if we were going for a trail walk I might say, “Do you mind if we take a little detour. There’s supposedly an area a little ways off where some weird gravitational anomalies occur.” I get that part out of the way early, so later we can just walk a couple of minutes off the path and when I get there and a pinecone floats between my hands, I don’t need to give a big introductory presentation. This is also a better way to extend the magic of that quick visual moment, by setting it up hours or days earlier. This gives some more meaning to the trick but without dragging down the magic in the moment.

To be clear, I still think a presentation or context is absolutely necessary for cerebral tricks if you want them to be memorable. Visual magic is so primal in its impossibility that you don’t need to add too much for it to be memorable. But if you deal four aces into a square on the table and cover each ace with three indifferent cards and the aces go from each packet to gather at a central packet… that’s not something that’s going to be meaningful and memorable to people long-term unless you make it conceptually interesting by giving it a context they can relate it to. Otherwise, while they may enjoy it in the moment, the only thing they’re likely to remember about it a couple of weeks down the road is, “I saw a card trick.”

(One thing this post doesn’t address is a long-form, visual trick. Like a multi-phase coin trick where coins are appearing, disappearing and changing into different coins. I don’t have a ton of thoughts on these types of tricks because I just don’t like them that much. I think they diminish the impact of the visual magic by repeating it over and over. And I don’t think they work well with more immersive presentations either. Most of these tricks (not all) are in a kind of no-man’s-land for me where they don’t align with either the targeted visual tricks that I like or the intriguing cerebral ones.)