Alphablocks Text and Ideomotor by Proxy

/Whaddup?

Okay, so today’s post is a further exploration of the Alphablocks concept made famous (?) by me in this post.

Now, I try not to pimp my own ideas too much, but if you’ve been sleeping on this concept because you think it’s just a progressive anagram variation, I would encourage you to give it a second look. While there are similarities with a PA, I find this feels much fairer. And that’s because you’re never getting any definitive information from the spectator. In a PA, if the spectator says there’s a B in the word, then it’s clear there’s a B in the word. With Alphablocks you never get that clear-cut information. But you can still narrow down from a large group of words relatively quickly.

I’m posting about this again today because a couple weeks ago I had an idea to make the process much more usable and I sent the idea along to Warwick Harvey who worked on the original version of the Alphablocks tool and within hours he had figured out a way to bring that idea to fruition.

Go back and read the first Alphablocks post if you haven’t yet because it will help to have the understanding of how the basic idea works.

In that version of the tool, you were working off a list of words. Either a list of words you came up with, or a list of words the spectator came up with (as in the Mind Reading Dice trick).

In this version of Alphablocks (known on Warwick’s site as Alphablocks Text) you can do the same basic effect with any (relatively small) chunk of text. So you can do it with song lyrics or a poem or a recipe or the first couple paragraphs of a news article, novel, or speech. Essentially whatever you want as long as it’s not too lengthy.

Here’s an example of what it looks like in action

Ideomotor by Proxy

Recently I called up a friend and suggested we try something out over the phone. I asked her if there was a poem or a soliloquy she had memorized in school or something else she remembered memorizing when she was a kid. The best thing she could come up with (hardly a poem or soliloquy) was the lyrics to the Golden Girls Theme Song.

“Have you ever heard of ideomotor actions? Okay, so they’re like these unconscious, imperceptible movements that people make based on their own expectations. And then those movements get magnified by something you’re touching or holding. So, like, with a ouija board. That thingy moves because you’re expecting it to move and thus you make it move. Or a dowsing rod. You don’t think you’re moving it yourself, but you are. The classic example is with a pendulum.”

I had her grab a necklace with a pendant on the end of it and I showed her how if she held it like a pendulum and just thought “circle” or “line” she could get the necklace to move in a certain manner.

“But what I’m looking into is something way crazier than that. It’s called Ideomotor By Proxy. And what that is, is the idea that you can control a pendulum with your mind when held by somebody else. I know it sounds bananas but I’ve seen it work.

“So here’s what we’re going to try. I want you to think of any word in the Golden Girl’s theme song. Nothing too short. Nothing with just two or three letters. But you don’t have to pick out a word that stands out in any way either. It can be anything. We’ll just use a word from that song because it seems to work best with something you ingrained in your memory as a child. That tends to leave an imprint on the part of your brain that controls this ideomotor function. So do you have a word from the song in mind?”

I had her go onto facetime with me so she could see what I was doing on my end.

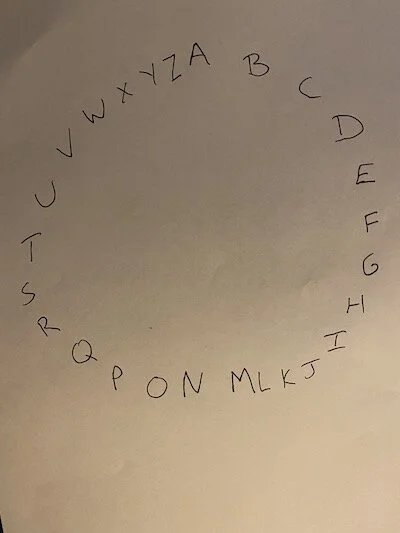

I showed her a piece of paper with the letters of the alphabet written in a circle.

I explained that I would hold my pendulum in the middle of that circle and she would think of the letters in her word on her end, and I would see what letters the pendulum was drawn to on my end.

“It might take a few minutes for it to get calibrated, but do your best to stay focused. I’ll try using different hands and holding the pendulum at different spots and we’ll see what gets the best results.”

I placed the phone in the middle of the circle of letters and held the pendulum above it and commenced the “first round.” From her perspective she just saw the pendulum moving in above the phone.

“Okay… the letters I’m getting are… E… N… V… and… maybe W too. Yeah, it’s bouncing around from E, N, V and W. Uhm… don’t tell me which letters, because I don’t want to know—I have to be totally out of the loop for this to work or else my own ideomotor effect will move the pendulum instead of yours—but were any of those letters in your word?”

No, she said.

“Hmm… okay. Let me try my other hand.”

In this round the letters were B, C, D, and G. “Are any of those in your word? A few or just one? Just one? Okay. Well, that might be luck or it might not. Let me try shortening up the pendulum.”

On the third round the letters were A, F, K, and T. Once again there was only one right letter.

“Okay, okay,” I said, cautiously optimistic. “That might not seem like it’s working. But if when I held the pendulum here we were just picking up on one letter, and when I held it at this point we were also picking up on one letter. So that means—if this is working—those would be the two far ends of a bell curve, which would mean the sweet spot should be directly between those two points. on the pendulum” Obviously I’m just making shit up here, but as long as it seems like there’s some process I’m following, then it doesn’t really matter the specifics of what I say.

I switched my positioning on the pendulum a final time. This time I’m held the phone with my right hand, pointed at me, while I concentrated on what was going on with my left hand and the pendulum. So she’s just seeing my reaction. “Oh shit,” I said. “I think this is really working. It’s moving totally differently now. Uhm… hold on. What is it… A… D…R…O…A… Adroa-something? Wait… R-O—Road?! Are you thinking of the word ‘road’?”

Her mouth dropped open and she ran her hand through her hair. “What?!” she said.

“Seriously?” I asked. “It worked? Wait… ‘road’ is in the Golden Girls theme song?”

“‘Traveled down a road and back again,” she said.

“Oh right! Holy shit.”

Method

When I had her on the phone originally and she mentioned the Golden Girls theme, I just kept talking to her while I did a google search for the lyrics.

I copy and pasted those lyrics into the text version of the Alphablocks tool here.

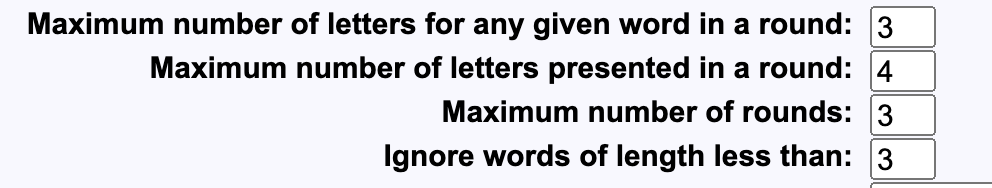

I like to set the parameters so it looks like this:

But that’s just my personal preference.

After a few seconds of processing, the tool gave me a few options:

When it says “rounds” it’s talking about how many rounds of letter guesses will be required.

So I could have said, “Think of any long word in the song… at least 8 letters.” And then I could have done the guessing in just one round. But because there are only three options for words that long in the song, it wouldn’t have been very impressive.

Looking back now, I probably would take the second option if I gave it a little more thought. I could have said, “Think of any word there. Nothing too short. Make it at least five letters long.” And then I could have got the word in just two rounds.

But in the moment I took the third option, which allowed me to do the trick with essentially any word in the song. (Well, any word over three letters.)

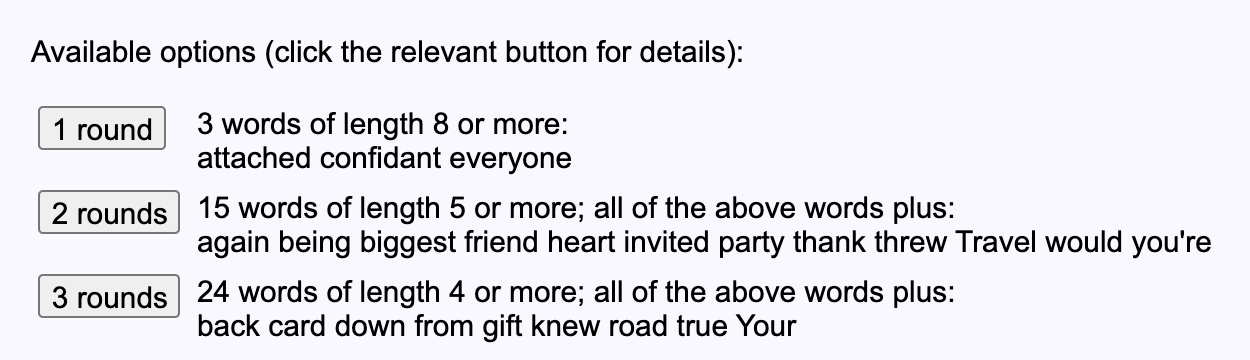

So I click that button and it gives me the chart which tells me how to proceed. It might look complicated, but once you familiarize yourself with how these charts work, you’ll see it’s very simple.

The results from three rounds I did with my friend were 0 letters, 1 letter, 1 letter. So if you start in that first column you’ll see 7 words will have 0 letters in that first round. Of those words, only Road and Gift will have one letter in the second round. And of those two, Road is the one that has one letter in the third round.

The pendulum works nicely with three rounds of letters. In the first round I hold the pendulum near the middle of the string. In the second round I move towards the end. If the results of the second round are better than the first, I move further in that direction. If they’re the same or worse, I move the other direction. Then, based on the results from the three rounds and apparently “triangulate” the perfect position.

As in the Mind Reading Dice effect, I want them to believe this might take many, many rounds to complete. So when it only takes two or three before it works, that should feel extra surprising.

I keep my laptop with the chart visible on it on the same table I’m doing the pendulum work on. I just never turn the camera in that direction once we go to facetime. That’s why I like having the phone in the middle of the circle for most of the rounds. It keeps the camera pointed at the ceiling rather than anywhere near the computer (not that they would know what they’re seeing if they did get a glimpes of the computer screen.) And it’s kind of an interesting angle, I think, for the spectator. Just seeing the pendulum dangling above as I call out the letters.

Keep in mind, this is just an example of one way to use the tool. You don’t have to use a pendulum. Does a pendulum work really well in this context? Yes. Is the concept of the ideomotor effect happening by proxy a great presentation? Yes. It takes something real that the spectator can research and verify is legit, and pushes it into the realm of the fantastical. It’s typical Jerx brilliance, what can I say?

But that’s just one way to utilize this tool.

How else might you use this, Andy?

However you want. Get off your ass and figure something out. Can’t you do anything for yourself? You need me to come over there and hold your little weenie for you while you take a piss and shake it off when you’re finished too? Warwick and I have done all the work here so far. Now you rattle a few of your own brain cells together and see what you can come up with, you lazy bitch.

Okay, byeeeeee!!!!!