The Box: Grocery Delivery

/I have a new tool to share with you today. But first, let’s put it in the context of a trick.

This is an expansion of an older trick I’ve written up somewhere before, but with some new tools and techniques involved.

Imagine

My friend Nataliya is visiting my apartment for a Taskmaster marathon.

At one point, I move some things on the coffee table and uncover a business card.

“Oh,” I say, pausing the TV, “you’ll find this fascinating. Wait… do I have one left?”

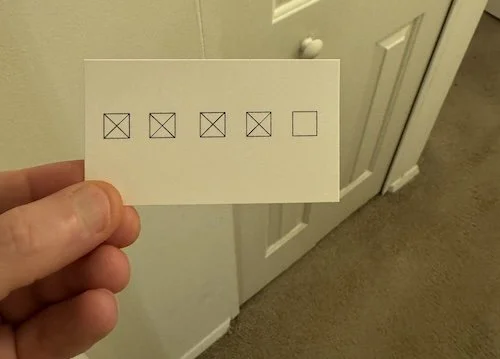

I turn the card over to show four checked boxes and on unchecked one.

“Okay, yeah I do. So, this is a grocery delivery service start-up that I’m part of the beta testing team for. It’s not like the typical grocery delivery service, because they only do one item at a time. But they do it in a kind of crazy way.”

I rub my chin. “Let me think what do I want…”

“Actually, I’ll let you choose. We’ll do it randomly, so you know it’s legit. We’ll pick something off my grocery list. I probably have 50 or 60 things on there—so let’s just say 50. Name a number between 1 and 50.”

She says 22.

I pick up my phone and open the list. “Okay, we’ll go with the 22nd item. Actually, I’ll give you some leeway—you can choose the 22nd item, the one above it, or the one below it.”

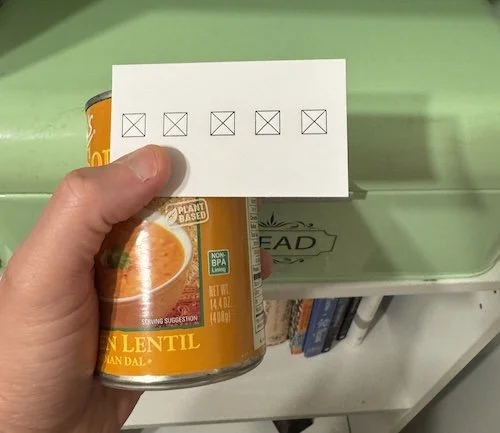

The 22nd item is beef jerky. Above it: granola. Below it: lentil soup.

“We can go with the item you chose. Or we can make it totally random—flip a coin to go up or down. Or just flip a coin in your head and tell me which one you land on. I’m harping on this because you’re going to think it’s some kind of trick. But clearly, everything on this list is different. If you’d picked a different number, you’d have landed on something else entirely, and different options.”

Eventually, she settles on the can of lentil soup.

“Here’s where it gets weird,” I say, leading her into the kitchen.

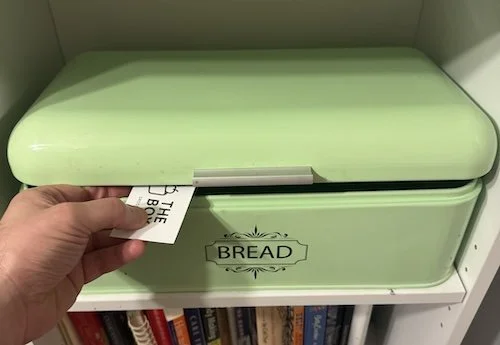

“This service delivers whatever single item you’re thinking of… right into the breadbox.”

I slide the card into the breadbox.

“It takes about a minute,” I say.

We awkwardly wait that minute out.

“Okay, check,” I tell her.

She opens the breadbox and pulls out two things:

A can of lentil soup.

And The Box delivery card—now with all five boxes checked on the back. (Sadly making the moment unrepeatable.)

Note

Keep this in mind…

The number is freely named.

The grocery list is a real note in your real Notes app.

The choice between items is free.

There is nothing else in the breadbox. Nothing is loaded into it at any point (other than sliding the card in).

They can open every cupboard, the oven, the microwave, or anything else in your kitchen and not find a single other thing from the list anywhere else.

Method

Here are some of the techniques used to make this so strong.

Fencing

As discussed in yesterday’s post, we’re using a technique called Fencing—framing the conditions as more limiting than they actually are. Then, when we loosen those conditions just a little, it feels like real freedom, even though the outcome is still tightly controlled.

I start by implying I’m the one who will decide what to use the card for. Then I "concede" some control by letting them choose a random number. From there, I open it up even further: they can choose the item at that number, the one above, or the one below

This is clearly not as free as letting them just think of anything you can get in a grocery store. But it’s significantly more fair than what I initially lead them to believe which is that I’m going to be the one who chooses something “at random.”

Bi-Reveals

As I wrote about last week, Bi-Reveals let you force two (or more) items, giving them a free choice at the end, while still allowing you to name or imply the reveal location in advance. That’s what gives the reveal its power because it feels like you’re committed from the start.

In this case, the implication comes from the name of the delivery service: The Box Grocery Delivery.

So when the chosen item shows up in the breadbox—the only thing in the kitchen actually called a “box”—it makes perfect sense.

If she’d picked the granola, I would’ve taken her outside to show her how the service works: you drop the card in the mailbox and wait a minute

This too is perfectly logical. It’s The Box grocery delivery service. Things are delivered to your mailBOX. What could be more clear?

If she had picked beef jerky, I would have walked her over to my front door. On a table next to the door is a small cardboard box. I would drop the card on top of the box, wait a minute, then tell her to open it.

Again, a fully logical reveal tied right into the name of the delivery service.

And in no circumstance do the other locations occur to someone. If I reach into my pocket to reveal something, it naturally occurs to people to wonder what’s in my other pockets. But if something appears in the breadbox, no one’s thinking, “Hmm, but what’s in the mailbox?” The other locations don’t even register as options.

And the sealed box near the front door draws no attention to itself. It just looks like a random piece of mail on a table near the front door, where people keep pieces of mail.

You might be thinking, “I don’t have a breadbox,” or even, “I don’t have a mailbox.” I get it. But you’ll figure something out. The real point here isn’t the props—it’s the structure. And more specifically, it’s the tool I want to show you…

The Damsel List Force

“Damsel” forcing is a term I use for a type of force that contains elements of clear, unequivocal, free choices.

The Damsel List Force is a Shortcut you can put on your iPhone. When run, it prompts you to enter a number. Once you do, it creates a grocery list in your actual Notes app, with one item at the selected number, and two other force items just above and below it

(You obviously wouldn’t have a big solo button on your screen for this. That was just for the demonstration.)

This tool works particularly well with Bi-Reveals. If you have two potential options, you say, “Name any number, but before you do, I don’t want you to think, ‘Oh, everyone must name the same number.’ So name a number to decide a postilion on the list, and then we’ll flip a coin to decide if we go one up or one down from there. That way, no one can say for sure what we’ll end up on.”

If you’ve got three reveals, you can do what I did: let them stick with the one they “chose,” or allow a coin flip (real or imagined) to shift it up or down.

The shortcut was created by supporter Albert Chang, and can be found in the resources below. It’s currently set up for this trick, but it’s well annotated and easy to adapt for other routines.

You’ll need to figure out your own preferred way to trigger the shortcut, but otherwise, it’s ready to go.

Wrap Up

That’s it.

The only other detail is how the final checkbox gets marked off on the card. I just switch the card early on, swapping the one with four checked boxes for one with all five at any point when they’re not paying attention. After the switch, the card sits on the table, face-up. The other side is out-of-mind until the end, when the final box appears checked (and now you have a rationale for not doing it again).

Thanks again to Albert for creating the shortcut and letting me share it here.

Resources

Printable business card pdf — For use with cards like these, which are pretty good for creating fake little businesses and institutions for magic premises.)