Name-List Victims

/I received an email from supporter Philip S. recently describing a use for the DFB app. DFB is an app that allows you to force anything at a numbered spot on a list in your notes app. (If that’s not clear enough, look it up.)

Philip’s email started:

I came up with a use for DFB that has got some pretty nice reactions. It puts a few different Jerxian concepts to use, so I wanted to share it with you.

Philip has allowed me to share that trick with you today. There’s a part of this trick that I think makes it particularly interesting and intriguing to people. (The most “Jerxian” part of the trick, in my opinion.)

But before we get to that part I need to set the stage. Don’t give up on the idea before then.

The Basic Effect

This is not the interesting part. This is the effect in its most basic form.

You ask someone to think of a number between 1 and 100 (or some upper-limit lower than 100).

They name a number—16 for example—you open up a list on your phone of your friend’s names, and at 16 is the name of the person who named the number.

(It doesn’t have to be just your actual friends’ names. You can make up some names. If it was all your “real” friends the number would be capped at what… six or something? Like if you count your mom as a friend.)

So this is a fine trick. Not earth-shattering. Who knows, it might get a better response in its basic form than I imagine. But at the very least it would be fine.

The Presentation

Again, this isn’t the interesting part just yet. (Well, it’s as interesting as you make it.)

Rather than just asking for a “random” number, it’s going to be much more compelling if that number has some meaning to it. There’s really no limit to the ways you could do this.

Here was Philip’s original idea.

Start with some Imp that could make sense as a psych-force. You then ask them to close their eyes, and imagine they're at the top of spiral staircase, so they can't see how far down it goes. You then have them count the steps until they get to the bottom, then have them tell you the number of steps there were.

You then explain the concept of a psychological force, and that you've been practicing methods for doing it. You show them your notes app, where you have a note titled "Psych force practice". It's a numbered list of names […] And of course, their name is at the number they named.

I like that. The spiral staircase imagery works well with the concept of delving deep into their mind.

But again, it can really be any reason to have them name a number.

“I’ve become very good at guessing my friends’ least lucky numbers. And I had a flash of insight of what yours might be the other day. If you had to pick a least lucky number between 1 and 100, what would yours be?” And then you go on to open a list of “Friends’ least lucky numbers.” Or whatever.

So come up with some way to get a number that’s slightly more exciting than “think of a random number,” and you’re good to go.

The Exciting Part

Here’s the part I really like. Let me go back and reprint Philips description of his trick unedited this time.

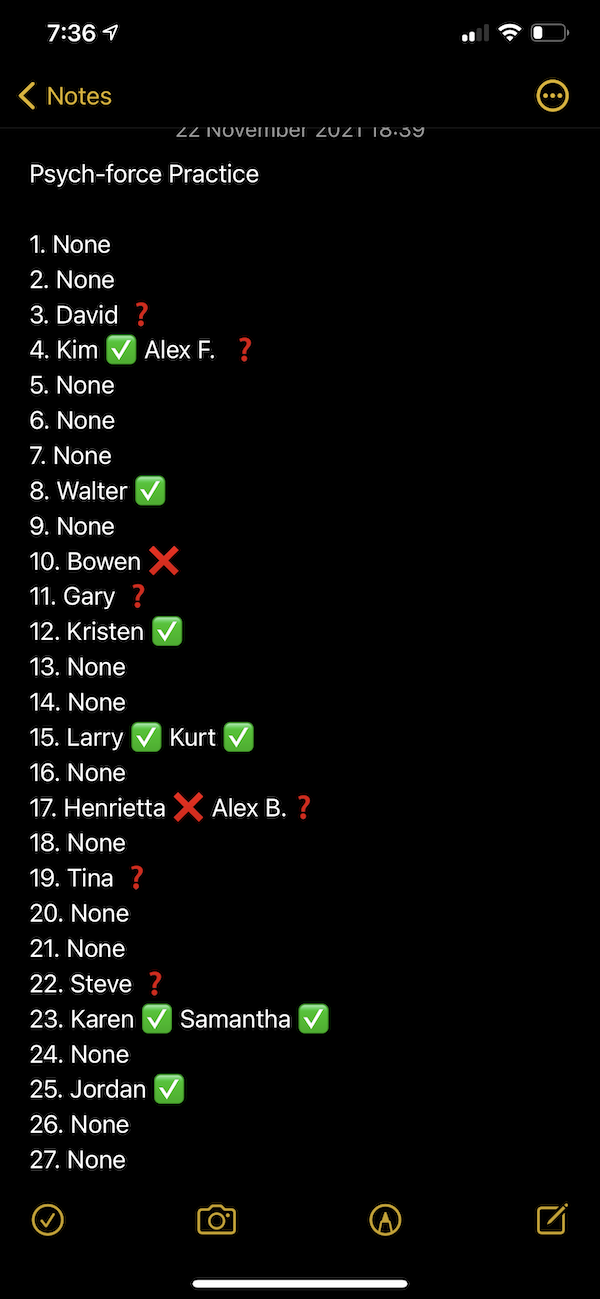

You then explain the concept of a psychological force, and that you've been practicing methods for doing it. You show them your notes app, where you have a note titled "Psych force practice". It's a numbered list of names--some have green check marks next to them (indicating you succeeded for that number/person) and some have red X's (indicating you tried and failed that time), and others have question marks. And of course, their name is at the number they named, and you delete the '?' next to their name and replace it with a green box.

As I wrote back to Philip:

The addition of the check marks, Xs, and question marks really takes this to the next level of what would otherwise just be a good but unremarkable trick.

Since the implication is that you have certain numbers you think will work for certain people, it may make sense that many of the numbers say "none" or "blank" or "N/A" or something. And maybe some have more than one person's name.

As Philip responded in his email back to me, setting up the list in this way makes it look much more like some sort of legitimate practice log, than if it was just a list of 100 names.

I particularly love that moment in Philip’s ides where you change the person’s ❓to a ✅. That’s a perfect little cherry on top of the effect.

You see what we’re doing, yes? In the Jerx vernacular, this is a Rep. Something that happens after the climax of an effect that adds to the world the effect lives in.

This takes what would be a very concentrated magic moment and then bukkake’s it outwards over (apparently) a bunch of different people and places and times in the past and (presumably) the future. This is a list of people that have been involved, and there’s been successes and failures and others you have yet to get to. This isn’t just a one-time thing. (With most effects you would want them to feel like a one-time, special thing. But this effect is improved by making it feel like there is a history to it.) This is an on-going story of a magical phenomena that they are, at this point, passing through.

These are the sorts of things that I’ve found cause an effect to really worm its way into people’s minds. They don’t necessarily affect the intensity of the initial reaction. They affect the duration.

Compare this to, say, using DFB to force Superman and the 4 of Clubs, and then turning around your prediction to show Superman holding the 4 of Clubs. Okay. I’m sure that gets a fine initial response. “Neat! That’s Superman and the 4 of Clubs.” But there’s really just a thud to that type of effect. “Here’s a random image of random elements with no connection to anything else. From some random lists that no normal human would ever have on their phone.” It’s the sort of thing that’s going to be of limited staying power. And there’s nothing really wrong with that. A magic trick can just be a neat moment. But if you have more “Jerxian” aims with your tricks, you might want to consider a trick using this format.

Thanks to Philip S. for sending along the original idea to me and allowing me to share it with you.