Help Wanted: What's the Worst Force You Can Think Of?

/In this post I wrote about the concept of having a bad marked deck, and why you might want to create one in order to corrupt people’s understanding of what a marked deck is. I enjoy this type of thing—planting seeds for things you won’t harvest until some time has passed. If I ask people if they’ve ever seen a marked deck, most haven’t. And if I introduce the Bad Marked Deck to them, and they believe that to be what marked decks are like, I can then use a good marked deck in the future and—with any luck—they will dismiss the possibility of it being a marked deck because it’s not used in a manner that they would associate with the deck I’ve shown them.

The idea being that people already know about marked decks, so now I want to poison that knowledge in some way. It wouldn’t make sense to introduce a concept to them, and then try and undermine it. But if they already have heard about something, I want to make that thing seem more inadequate than it really is.

You’ll sometimes see this done with the concept of “palming.” Laypeople have already heard of palming so sometimes magicians will mention it in their presentations (such as with the Invisible Palm effect) and demonstrate it in a way that it seems like it wouldn’t fool anyone. That’s the sort of thing I’d like to do with every magical concept laypeople are familiar with.

(By the way, if you’re a supporter of this site, the Jerx Deck you’ll receive next year in your supporter package is going to be a bad marked deck. Not “funny” bad. But just overly-complicated bad.)

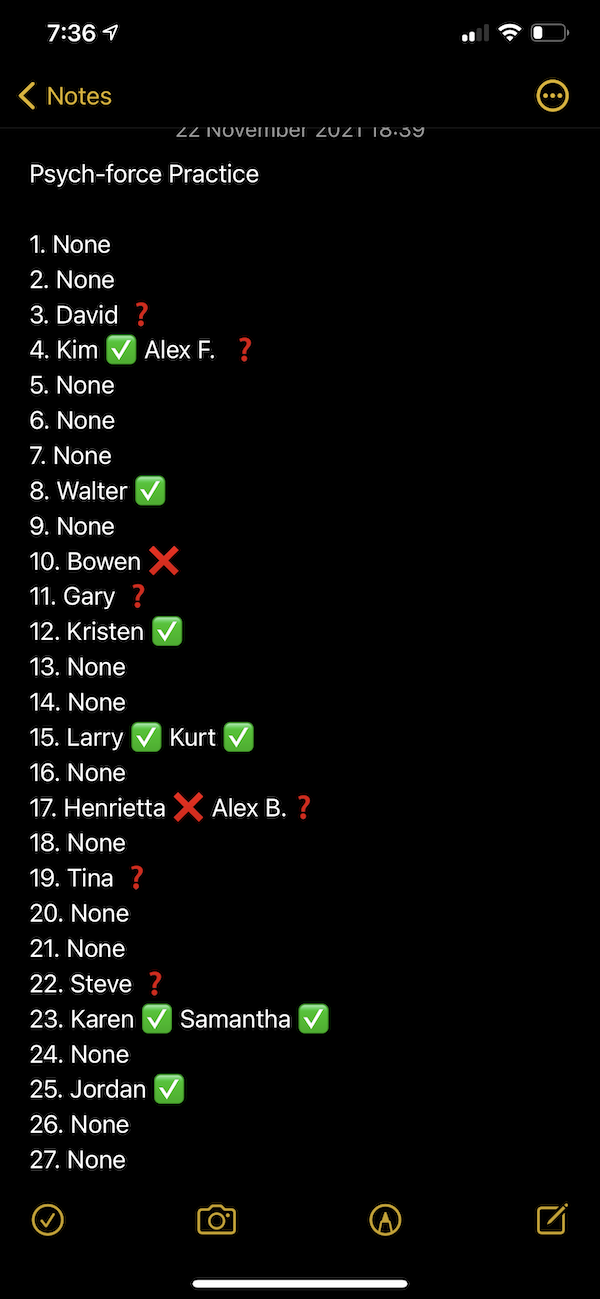

So now I’m thinking about ways to do that with card forcing because I’ve recently been doing a number of effects that start with me performing and explaining a shitty version of the trick and then following that up with a similar effect but with a completely different method. This structure seems to generate much stronger responses for me than just doing the better version in isolation. (For more details on this, see this post. Or, if you’re a supporter of the site, see the essay “Garden Pathing” in issue 2 of this year’s newsletter.)

Since I’ve been teaching a lot more crappy tricks, many of which require a force, I need to identify some bad forces that meet these criteria:

They fool people to the extent that it’s not completely obvious how the card was forced.

BUT

The selection process is unnatural/needlessly complicated in a way that makes it obvious this isn’t a truly “free” selection.

AND

Exposing the force wouldn’t reveal any useful deception techniques.

The first thing that came to mind was the 10-20 force, because, as it’s generally described, it’s fucking stupid. “Name a number between 10 and 20,” is no way to start off anything that’s supposed to feel free or random in any manner. At least not when you’re holding something with 52 options in your hand.

And, of course, and process that forces a number could then be used to force a card by counting down to that number in the deck.

But I’m still looking for some more bad forces. So if you know of any (or can create one), send me an email and let me know.

Combining exposure and weak methods is a powerful concept. Teaching them a method, even if it sucks, gives them that little dopamine hit of learning a secret. But it also takes them further away from the sort of methods I’m going to be using. Since they already know of the concept of card forcing, I want them to believe it amounts to literally forcing a card into someone’s hand from a spread (a la the classic force), or that it requires a very convoluted process. That way when they’re just cutting a deck, or touching a card freely, or stopping me while I deal—they’ll be less likely to even conceive those actions could be part of a force.