Uglying Effects

/When you do a well-polished, lovingly-structured effect for people in social situations, they can’t help but picture you practicing this and refining it before you show it to them. You, sitting in front of a mirror, counting coins into a little brass box doesn’t make them think “mystery” and “wonder.” It makes them think, “dork” and “no prom date.”

Frequently, one of the strongest things you can do for a trick is to ugly it up.

I’ve hit on this a lot in the past when talking about patter. If your story is too smooth, it comes off as rehearsed. And that’s not helpful if you’re trying to create a feeling of “we don’t know what’s going to happen next.”

But it goes beyond patter. That feeling of things being too “clean” can be baked into the structure of a trick as well.

Today I’m going to show you a specific example of how I messed up the structure of a trick I liked to make it markedly more powerful for social situations.

You’re going to need a few minutes to watch a video to understand this, so if you’re at work or mid-funeral or something, circle back later.

The trick is called The Pink Lotus, and it comes from the Charms Deck project by Nikolas Mavresis & David Jonathan. You can see the performance on the product page for the effect (third video) or watch it below.

The trick uses a deck of good luck charm cards and a few bad luck cards.

In the original handling, the deck is cut at the beginning. Then five good luck charms are mixed with five bad luck charms. The spectator separates the cards face-down, and it’s revealed they’ve separated the good luck charms from the bad luck charms. Then we reveal the card they cut to earlier is actually spelled out by the imagery on the good luck cards.

It’s a strong reveal, but structurally the trick is a little too “tidy” for it to come off as anything other than, “this is how it was always going to play out,” which undermines the strength of the effect in my opinion.

Here’s how I uglied it up for social performances.

The setup

The “LOTUS” spelling cards are face-down in the box. On top of them, five bad luck cards face-up. Then the rest of the deck above that.

I bring out the deck and remove everything above the bad luck stack.

I show it to be a deck of good luck charms. And explain how it’s designed as a deck that allows you to find a good luck charm for yourself and then test it to see if it really works.

I start by forcing the Lotus card on them. This can be done through an extended procedure or just by having them touch a card. Instead of waiting to the end to reveal this card, I reveal it up front. I give it a purpose. We are going to test if this is a genuine lucky charm for them.

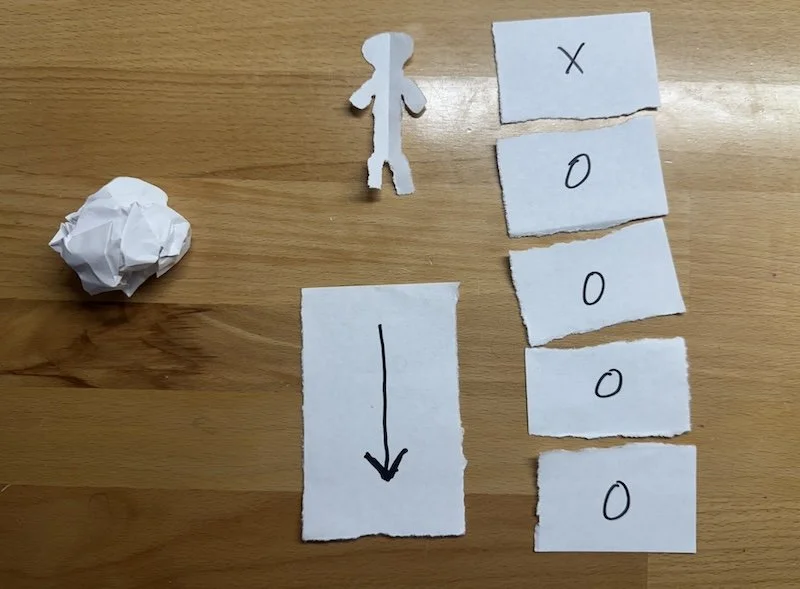

“Okay, so you were drawn to the Lotus. Now the next step is to test this. We need five other random cards. It doesn’t matter what they are. Just touch any five.”

I have them touch any five cards, which I strip out and place on top of the deck (still face down).

“We’re also going to use five bad luck cards.”

I dump the cards from the box onto the deck face-up, which secretly brings the LOTUS stack into play under the bad luck cards.

I show the bad luck charms, describe them quickly, then flash the five good luck charms they “chose” as well. I don’t bother to explain each one because my attitude is that it doesn’t matter what they are. This prevents the notion of a switch coming to them, since I don’t seem to even care what those cards are.

I “mix-up” the good and bad luck cards and we test their chosen card (the Lotus) by seeing how “lucky” they are at separating the good cards from the bad cards while they rest their hand on the Lotus card. At the end, it’s revealed they separated them perfectly

“That’s crazy,” I say. “I’ve never had it work out that well. I’m going to take a picture of this”

I snap a photo of the layout.

And… that’s the end.

What has happened here? They were drawn to one good luck charm card. We tested it. And it proved to actually be lucky for them.

Story-wise, this is actually much simpler and more straightforward (and hence, stronger) than the original version. Story-wise we’re cleaner. It’s effect-wise where it’s going to get uglier and less structured in a moment.

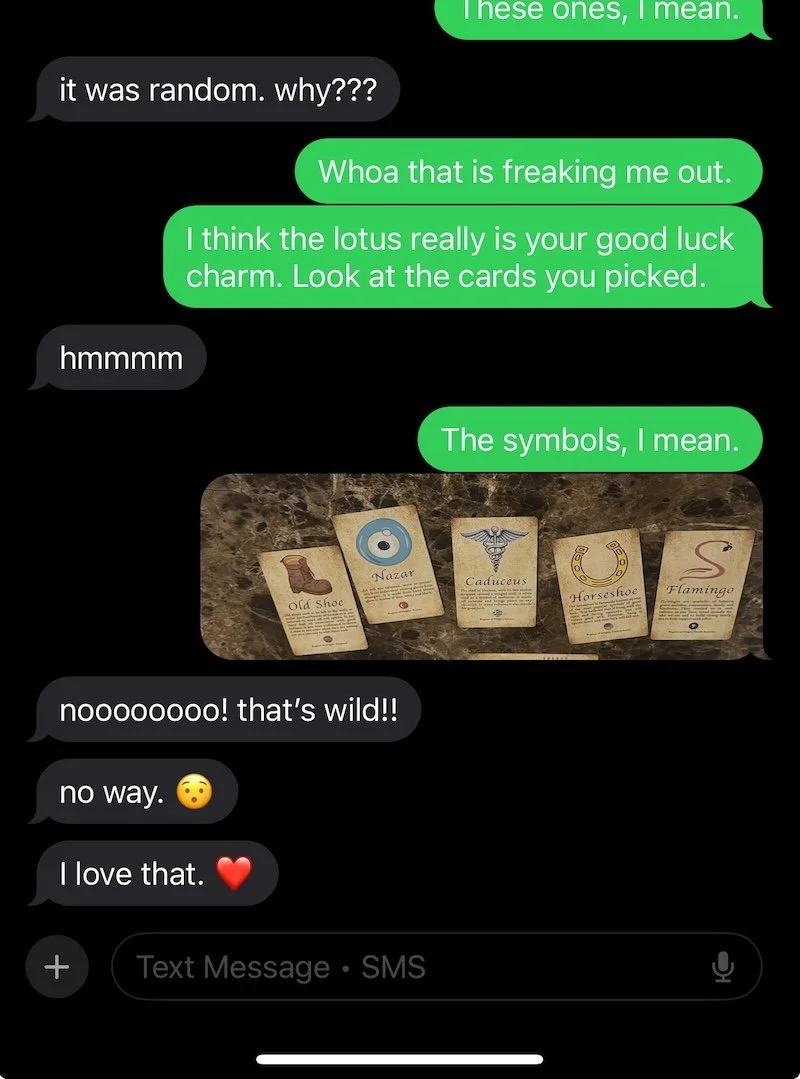

TWO DAYS LATER

The original routine is a tidy little four-minute package.

What I’ve done is cleave it in two, left the climax dangling, and let it resolve itself days later.

It’s definitely a messier structure—“uglier” by design—but it’s also more powerful. And as a social performer, that’s the only metric that matters.

The original feels like a clever trick. But even if people don’t consciously recognize it, on some level it’s obvious that the only reason that card was cut to at the beginning was so you could show the other cards spell it at the end. It’s a neat moment. But it’s a very magic-trick-y logic and structure.

By uglying it up, that climax feels fully unplanned. It resonates as an aftershock of genuine weirdness or coincidence—the kind of thing people keep thinking about long after the moment.

And that’s the bigger point: the “prettiest” tricks are usually the easiest to dismiss. Their edges are too neat, too defined. People can pack them away in their minds as a harmless little puzzle.

Ugly tricks can be much harder to shake for people

A pretty trick is like your dog leaving one solid turd on the hardwood floor: something to deal with, but easy enough to scoop and forget. An ugly trick is more like doggy diarrhea smeared deep into the shag carpet. It lingers. It stays with you.