My Biggest Testing Takeaway

/A friend showed me a card-to-pocket routine he was working once, and I told him that he needed to draw attention to the fact that his hand is empty before he removes the card from his pocket.

“I am,” he said, “I show my palm empty like this before I reach into my pocket.” He held his hand out, palm facing me, and fingers spread wide.

“No,” I said, "you need to tell them to take note that your hand is empty.”

“I don’t have to tell them because I’m showing them. I don’t want to insult their intelligence.”

“It’s not ‘insulting their intelligence.’ It’s making sure they take note of something they need to remember for the trick to be successful.”

He sighed, like I wasn’t getting it. “Would a real magician say, ‘Note that there’s nothing in my hand’?”

I looked at him. “Yes. That’s exactly what he’d say. Because a ‘real magician’ would be showing you this thing to demonstrate something And thus he would want to make sure everything was as clear as possible.”

I probably didn’t use the word “thus” when this actually happened. But it was something along those lines.

I was asked in an email which of the testing results had the most profound impact for me personally on my magic. After thinking about it, I don’t think it was one specific thing we tested. But something that came through over and over across the time we’ve been testing.

In 1000s of performances and interviews with spectators, when a trick would fail, it was very rarely because they saw something they shouldn’t have. Like they spotted a double lift. Or a card being palmed.

The vast majority of the time, when a trick didn’t hit it was because we failed to make crystal clear one of the conditions that made the effect impossible.

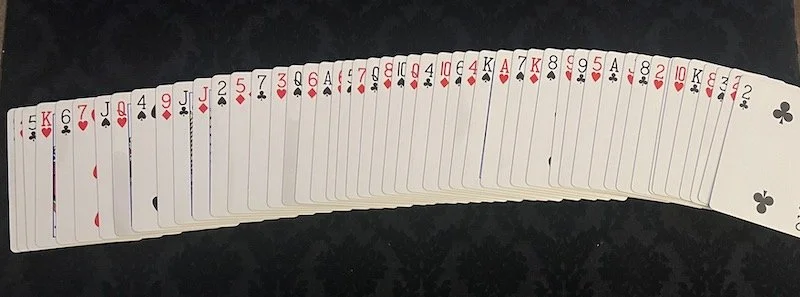

In Wednesdays post I mentioned a trick we did where the method was “obviously” a false shuffle (the magician called off the cards from a shuffled deck). And, in fact, when asked what they thought the method was, 80% of the respondents suggested that the cards weren’t really mixed. But what did the other 20% say? Well, a few would just say they had no clue. Then there would be a couple people who would suggest something needlessly elaborate, like hidden cameras and secret earpieces sending information to the performer.

But a lot of the remaining 20 percent would say something like, “He probably had the order of the cards memorized.” And when we’d talk with them to get more clarity on their answer, we’d say, “But he shuffled the cards.” They might say, “Ooh, yeah…” or, “Did he?” The shuffling didn’t stick with them.

You might think someone shuffling a deck three or four times would be enough for people to remember the cards were shuffled. But I can tell you that frequently it wasn’t.

Laypeople don’t watch magic tricks the way we do. I find it much easier to perform for magicians, because I know how they watch effects and what they will pick up on. But laymen are different. They don’t always note the things that we think might be obvious. You need to focus them to create certainty. Because if they’re just pretty sure the ring was threaded on the string, you don’t have much of an effect. They need to be certain of it. Or else they’ll tell themselves, “I guess the ring wasn’t really on the string.”

I now believe that it is almost impossible to over clarify the conditions of an effect (unless you’re trying to be annoying).. Saying “notice that my hand is empty” or “there’s nothing in the card box, is there” or “all of these cards are blue” may feel kind of hokey or unnecessary. But in all the issues we’ve catalogued people having in our testing, I don’t recall a single time someone suggested they felt condescended to by the magician clarifying or highlighting the conditions. But there were countless times where a trick didn’t get as strong of a reaction as it could have because they didn’t notice or remember something we thought should have been clear.

That’s what I took away most from the testing. Whatever type of magic you’re doing, the effect comes down to something happening in defiance of the conditions you established. So don’t be coy or subtle about establishing the conditions. And if the method you’re using doesn’t allow you to firmly establish those conditions, it’s probably not a strong enough method for that effect.