The Audience-Centric Mindset

/Last month, I was writing an essay for another magic book (not one of my own) about how to maintain a casual vibe when performing for a larger group of people.

It’s easy to keep a casual tone when you’re performing one-on-one (although most magicians still fuck that up because of social awkwardness).

But when you’re performing for 6 or 10 people, or something like that, it can be difficult to maintain the feeling that you’re a part of the group.

When I’m in this situation, what is the nature of the relationship I’m shooting for?

I don’t want to feel like The Magician at center stage.

I don’t want it to feel like they’ve come to the Holiday Inn to hear me give a presentation on time-shares.

I don’t even want it to have the dynamic where, like, we’re a group of neighborhood women, and I’ve invited them over the house to sell them some Pure Romance products.

(Pure Romance is a funny name for a company that’s primarily known for selling sex toys. There are a lot of words I would apply to the process of using a set of graduated butt plugs to incrementally gape my asshole, but I’m not sure “romance” makes the list.)

What I’m saying is, I want to do whatever I can to make my role in the group as close as possible to the people I’m showing a trick to.

But, of course, I’m the one showing the trick, so it’s hard for it not to seem like I’m the one “in charge” or that I’m in a “special” position.

Here’s one of the thoughts I try to keep in mind in these situations to try and maintain the most casual relationship between myself and everyone else in the group. I imagine that they’re all students. But I don’t imagine myself as their teacher. I imagine myself as another student. There is no teacher. The teacher had to leave class abruptly. Her kid just got run over by a bus or something (that part of the analogy doesn’t really matter). She tossed me the lecture materials before she runs out the door and asks me to continue on with the material while she’s gone.

So I have information that the other people in the group don’t have. But I’m no expert. I’m going to stumble my way through it and do my best, but I don’t know exactly where it’s all going. And when it comes to interruptions and interjections, I’m not just going to tolerate them, I’ll encourage them. Because I don’t really want to be the leader of this group. I want other people to help us get through the rest of class.

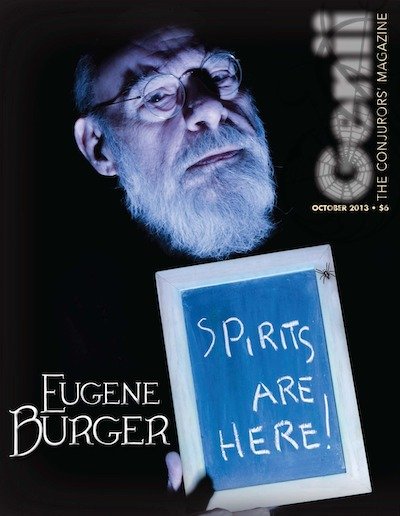

This is the vibe I’m going for when performing something for a larger group of people. I’m not here to lecture them. I just have some information they don’t have, and we’re going to work through it together. That’s why I frame so many of my tricks not as a demonstration of my skill, but as something I want to “try.” It’s something I read about in an old book, or saw on television, or heard on a podcast. It’s something my mentor in magic is trying to teach me. Or something I learned at a convention where they gather a bunch of different people with arcane knowledge. Or it’s something my magician friend sent me in the mail.

If your science teacher says, “Let’s try this experiment I heard about. I have no idea if this will work, but it’s supposed to be pretty cool.” Then, for the duration of that experiment, he—partly—becomes part of the student group.

This is the Audience-Centric approach to performing. You diminish the role of The Magician by making yourself as much a member of the “audience” as possible.