What follows is the general progression I take when first meeting someone to get them accustomed to, and then hyped for, more immersive presentations in magic. This is not set in stone, and it's not always the same, but it will give you some idea of how I build up some of the styles and techniques I've written about here.

This is not something that happens in one night. It happens over a number of days, if not over weeks or months. And this is just what I've found works for me and the style I'm trying to gear them towards. This little algorithm of steps may not work for your style or your goals.

I'm going to provide you the general steps I follow and then give you a specific example from the last time I went through this process a couple months ago. This process is something you will use on people who are likely to be in your life long-term (new friends, co-workers, etc.) You're grooming them. Yes, like a sex predator with his favorite cub scout, you're systematically introducing new ideas and activities to people, a little at a time, until they've bought into your world. But you're a good kind of predator. You're only going to fuck their mind.

Step One

The last thing I want to do is say, "Hey, I do magic... want to see a trick?" I think that goes along with people's worst instincts about magicians: that they're weird show-offs. Instead I want it to seem like I never would have mentioned it if they hadn't brought it up. I have a bunch of these techniques that I call "hooks" that I'll get into in the future. I would also recommend the essay, "She's Gotta Have It," in the JAMM #1 for some more of these techniques.

So step one is to set out a hook. Properly done—with a person who has a modicum of interest in talking to you—you can almost always use some sort of hook to have them seemingly guide the conversation to magic.

Most Recent Example

I was at a cafe talking with a girl on one of the couches. I was wearing my GLOMM Elite membership shirt, which is a much-used "hook" for me.

At one point she pointed to my shirt and said, "I like your bunny."

"I like your pussy," I said, pointing at her crotch.

No. I'm kidding. That's not how it went.

She said, "I like your bunny," and I said, "Oh, thanks."

"What is that shirt? Is that a real thing or...."

"Oh yeah. It's the Global League of Magicians and Mentalists. It's the largest magic organization in the word. I'm a member. Well... everyone who's into magic who isn't a sex offender is a member. So I'm in."

"Is it... like, a joke?" she asked.

"No. No joke. I'm really not a sex offender. Oh... the shirt. Uhm... no, it's not really a joke."

"So you do magic?"

Boom. And now we're talking about magic. And she brought it up. Yes, the shirt is obviously a big invitation, but it's an unobtrusive one.

Step Two

I don't want the idea of me in a top hat and a cape shoving bunnies into boxes to be an image that hardens in the cement of people's minds once they learn I do magic. So I try to disrupt that thought but still keep expectations somewhat low.

Example

She asks if I do magic.

I say: "Like tricks? Uhm... yeah. When I was a kid I used to be really into it. I still do some stuff now but it's probably not what you're thinking. Similar concepts but just... different."

This is all just nonsense. I just want their understanding of what I do to be a little nebulous. I found if I just answered the question, "Do you do magic?" with a "yes," sometimes I would get the sense that they were like, "Oh. I know what that is. I don't really like that." So now I try and keep it a little vague.

This almost universally gets them to ask me to show them something. Again, this all feels like their idea.

Step Three

"Can I see something?" the person asks.

"Oh, yeah sure," I say. "Uhm... yeah...actually there's something I've been working on that I could use your help with."

This is classic Peek Backstage technique. By saying it's "something you're working on" you've eliminated any potential weirdness of you as "the Magician." This is just a work in progress that they're helping out with.

Now the first trick you show them should be something simple and direct.

Example

Most recently my opening trick was a two-coin, coins across with quarters.

Step Four

The next trick I perform for the person (often days later) is done in the Peek Backstage style as well. But this time I say, "Oh, can I try something with you? You'd be perfect for this."

This is subtle, but when you tell someone "you'd be perfect for this," you're not only telling them something that feels somewhat complimentary, but you're also planting a seed. And that seed is that these things you're showing them are not just things you could do for anyone at anytime. This is something that's going to work well now because, YOU specifically are here with me. It's not just something that happens automatically. (This is the first step in messing with their understanding of how magic tricks work.)

But what do you do if they ask what you mean when you say they'd be "perfect" for it?

I say something like, "I think you have the right energy. And you strike me as perceptive and imaginative, which is, like, the ideal person for this sort of thing."

This is kind of meaningless, yes. But it's positive. And I have no issue with meaningless positivity.

Example

My 2nd trick, most recently was the 10% Peek which is simply my version of a peek of a chosen card.

Steps Five and Six

At this stage I like to do a couple of tricks in the Distracted Artist style. That is, tricks that are seemingly happening without me intending them to.

This further screws with their concept of how tricks work. Notice I'm not trying to convince them it's not a trick. I'm just trying to play with their notion of the nature of magic methods. Could you have spent so much time practicing vanishing a coin in your youth that now you sometimes accidentally vanish a coin? That doesn't seem likely with most people's understanding of how these sorts of things work. But that's exactly what I'm trying to imply to them: Don't get all hung up on how a trick is being done. You have no idea how this stuff works in even a general sense. So don't get worked up about the particulars.

In fact, the Distracted Artist thing is a kind of outlandish concept, and if it was presented as a trick it would be easy to dismiss. But when you don't make a big deal about it—maybe you're even a little annoyed or embarrassed by it—and you let the moment pass with very little fanfare, the whole thing becomes harder to reject completely.

The thought process I'm trying to instigate in the person is, (with a coin vanish, for example), "Well, I know he didn't 'accidentally' vanish it into the ether. But... it doesn't seem like you could accidentally do sleight of hand either (from what I understand). So maybe there's something else going on here that I can't quite wrap my head around. Maybe he was just pretending it was an accident? But... to what end? If you wanted to perform a trick you'd ask for people's attention, not just let it happen. Right?"

Example

Most recently for this stage I vanished a pen (apparently unintentionally), and balanced coins on top of each other (apparently absentmindedly).

Step Seven

Next I do an Engagement Ceremony style trick (remember, there's a glossary in the sidebar).

This gets people used to two things:

1. Longer tricks. This style will often go on for 10-15 minutes.

2. Me showing them things that I'm not taking credit for.

Both of these are things a spectator is not used to seeing from someone performing a trick for them, and they're both things that are foundational elements in many of the immersive tricks I perform, so this is a good introduction to them.

At the same time, the process of the trick is not so different from a typical magic trick. So I’m slowly easing the person away from their preconceived notions.

Example

Most recently the trick I performed at this step was Good St. Anthony from The JAMM #5.

Step Eight

In step eight I do a short-ish (three minutes or so), Reverse Disclaimer type of trick. "Reverse Disclaimer" is a term I haven't used in a while. It just means this... If I tell you I'm going to read your mind or predict the future, those are abilities people have actually claimed in the real world. So I might give a disclaimer to say, "This is just a magic trick, etc. etc." A Reverse Disclaimer trick is a trick where what you're suggesting is so absurd, the claim itself acts as a disclaimer that it's not to be taken seriously.

If I say, "I learned how to speak dog. I'm going to tell your dog how to find the card you selected." And then I start barking at the dog and he does apparently go and find the card, I don't have to follow that up with. "Just so you know. I don't really speak dog. That was a combination of magic, showmanship, psychology," blah, blah, blah. The claim itself lets everyone know they can relax because I'm just screwing around.

At the same time, the climax of the trick should be strong enough that for a moment they almost buy into whatever insane thing you're telling them. But again, that's only based on the strength of the trick, not the believability of the premise.

This stage is meant to introduce the idea that we can all know something isn't true, but we can still enjoy it and allow ourselves to get swept up in it and that that can be a fun experience.

(By the way, the upcoming JAMM will go into more detail on the dog trick.)

Example

Sunlight Bumblelily from JAMM #4 is the one I most recently used at this stage.

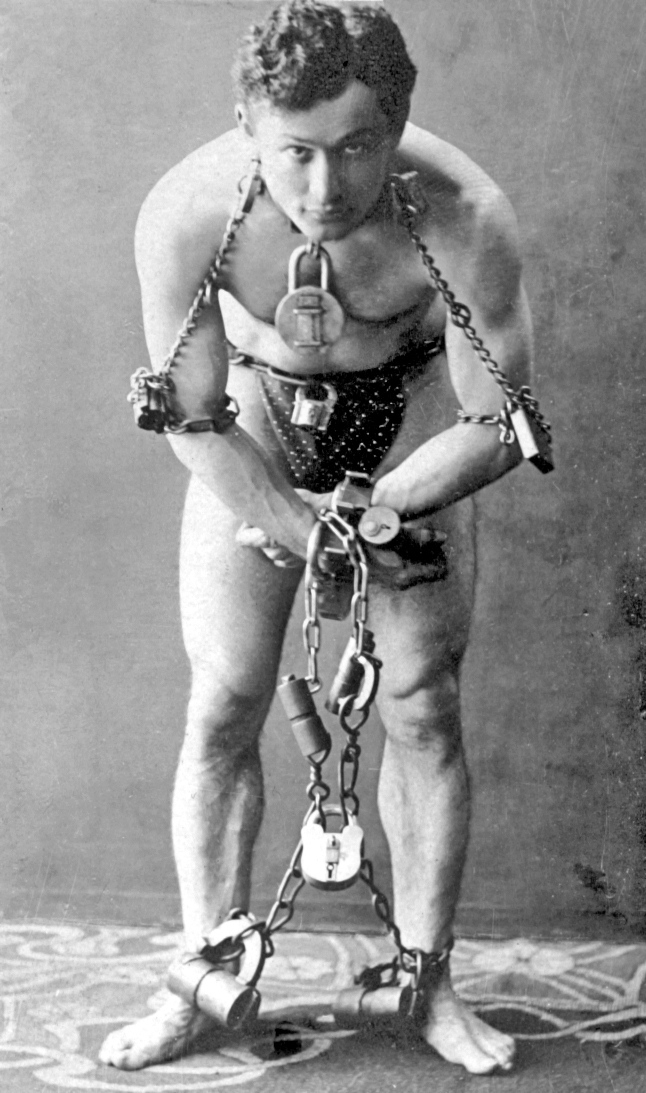

Invisible Palm Aces is one I used to do a lot around this point as well. The premise—that I'm absorbing the aces into my palms—is obviously ludicrous and not intended to be believed. But if you do the trick well, it can feel awfully real.

Step Nine

At this point people are kind of primed for anything. I've started them off with simple, easily digestible tricks. I've acclimated them to: messing around with their understanding of method, shifting the focus off me as the magician, engaging in tricks that require an investment of their time, allowing themselves to go along with a trick regardless of how ridiculous the premise.

Combine that with strong magic done with an audience-centric approach, where they understand this isn't about demonstrating how great I am, but it's about our interaction and generating these moments just for our enjoyment and not expecting something in return. Then, I've found, you can really lead people to go along with pretty much anything.

Example

I approached my friend and said, "Hey... this is going to sound crazy, but did you know there's a psychic ghost dog at America's largest pet cemetery?" And with that we were off on a little afternoon road-trip.

Could I have gotten her to join in on such a thing that first night? No. I would have seemed like a sociopath. Even half-way through this process I don't think the groundwork would have been laid sufficiently. But after the weeks, or even months, it takes to go through the full set of steps, I think you can build up the trust, and get people in the right headspace, for them to be on board with almost any kind of experience.

One final thing. Once I get people to this final stage that doesn't mean that I only show them long-form, immersive tricks. In fact I tend to kind of loop back around and start all over again from the beginning. The structure becomes very loose at that point. I just try to keep up the variation in styles and experiences because I think that's what makes it enjoyable long-term for me and them.