Further Fat Shit

/Required reading:

Failsafe Trick Examples

Fat Shit

I certainly never thought I'd be writing a third post about John Bannon's 51 Fat Chances—especially not after I mistakenly dismissed it completely the first time I read it.

What a lot of people don't like about the trick is that the final phase is done with the Down Under Deal. I understand why people dislike this: it doesn't quite feel random. The final card still feels random, but the process of arriving at it doesn't.

This idea fixes that final phase so it feels random and like the spectator had some influence on how it would play out. It also maintains the established pattern that turning a card over eliminates it.

Note: You'll need to be familiar with the original trick to follow this explanation.

We're at the end of the first part, where most of the deck has been eliminated. On the table are seven or eight cards.

If Seven Cards

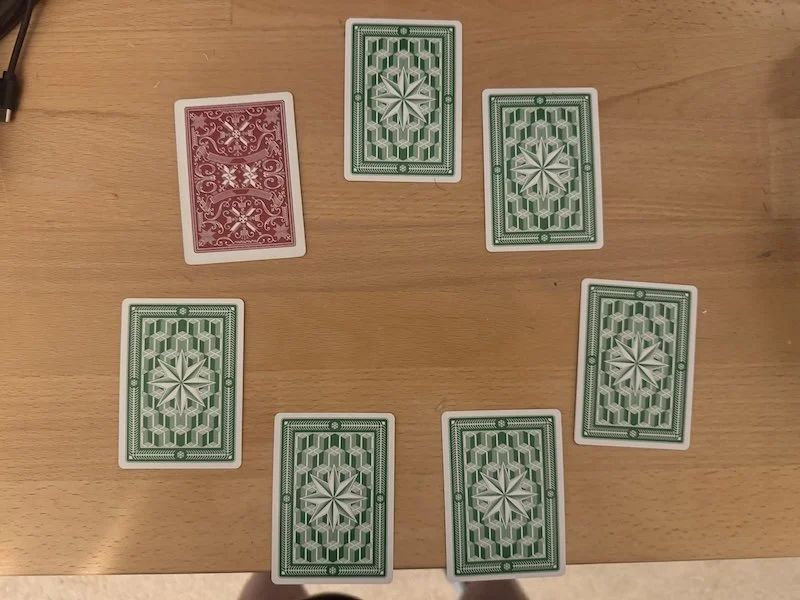

Deal the cards (or have the spectator deal them) in a circle, with the final card (the force card) at the position of the odd-backed card in the image.

Tell them:

"You're going to think of a magic word. Whatever word you name, we'll use that to spell around the circle of cards, starting here [the card at the 12 o’clock position] and going clockwise. We'll turn over whatever card we land on, eliminating it. We'll keep doing that until all the cards but one have been eliminated."

If Eight Cards

Deal the cards into a circle and tell them to slide any one out. They likely won't pick the last one you dealt (the force card), but if they do, you can end the trick there.

Otherwise, say:

"Okay, whatever the value of that card is, we're going to start here [indicate the top card of the circle—the one after the force card] and count around the cards clockwise. We'll turn over whatever card we land on, eliminating it. We'll keep doing that until all the cards but one have been eliminated."

Either way, we now have:

A circle of seven cards with the force card to the left of the card you indicated as the starting position.

A random, spectator-derived bit of information: either the number of letters in a word they chose, or the value of a card they freely selected.

Prime Number Principle

Now, via the George Sands Prime Number Principle, you can simply follow the procedure mentioned and it will leave the force card regardless of what value they choose or what length of word they name.

To be clear: you always count the eliminated cards as well—you don't jump over them.

Notes

The number used can’t be seven, because that would eliminate the force card immediately. So if they choose a word with seven letters or draw a 7 from the deck, start counting, then "notice" that it will bring you to the same card over and over. Simply have them name a different number or word. This doesn't feel like you're "denying" their choice—it's just clear you can't use the exact same number as the number of cards you have, or you'll always land on the same card.

✿✿✿

Alternatively, you could place your finger on the starting card and say you're going to start there and count (or spell) around the circle to their number (or word) and turn over the card you land on. Then you have two options for how the trick ends:

Option 1: "For example, what number do you have? Seven?" Count to seven, turn over the card, and act like that was how the trick is supposed to end.

Option 2: "For example, what number do you have? Five?" Count to five and turn over that card. "And we'll keep going on like this with the number you chose, turning over cards to eliminate them, like we were doing before, until we finally only have one face-down card left."

That's probably what I'll do, unless I specifically need the trick to end with the last card face-down.

✿✿✿

Six and eight don't look as good, because they will eliminate cards in order around the circle. It just looks less random.

You can choose to let it play out that way, or you can say, "Ah, if we count along like that, it's just going to eliminate cards in order around the circle. I'm fine with that, because that is what you chose. But if you want, you can pick a different word [or number]."

✿✿✿

From the spectator's perspective, they've either named a completely random word or freely selected a card—both choices that feel entirely under their control. The counting/spelling process mirrors the elimination pattern established earlier in the trick, creating a consistent logic. And because they can do most of the handling themselves, it removes you from suspicion entirely.

Compare this to the Down Under Deal, where you're mechanically dealing cards in a prescribed pattern that, while effective, feels like a procedure rather than a random process influenced by their choices.

With this modification, the result is an impossible-seeming slow-motion force that can be done almost completely in the spectator's hands. Perhaps there are more tweaks to come, but as it stands, it's very strong and nearly impossible to backtrack due to the multiple deceptions used.

Thanks to Oliver Meech, who first suggested to me the possibility of using the Prime Number Principle as a way to end the effect.