Until March...

/This is the final post of February. Regular posting will begin on Monday, March 2nd.

The next issue of Keepers will be sent to subscribers on Sunday, March 1st.

David E. writes:

I’ve never seen anything like the push for the Breakthrough System. It’s got a 15 page thread on the Magic Cafe and hasn’t even been released yet. It’s $125 for some downloads and that’s a “presale” price. And every mailing list I’m on seems to be pushing it: Daily Magician, Christian Grace, Mark Esldon, magicreview.org, Craig Petty, Lloyd Barnes and maybe more. What is going on with this thing? Do you feel left out?

No, I don't feel left out. Johannes (the trick's creator) asked if I would promote it on the site and I said I don't really do that. He then asked if he could sign up to advertise in the newsletter and I said no, and things kind of stalled after that. It probably didn't help that I sent him a link to me writing about another project of his where I said it was something you should only do if you want to seem like a "socially dysfunctional weirdo."

I think I often come off as unhelpful to people trying to market their stuff. 🤷♂️ I'm not trying to be. I just try to keep a guardrail up that prevents me from being influenced by people who offer me things for free. I want readers to know that if I'm talking up a product, it's because I'm genuinely using and liking it.

The Breakthrough System looks cool. I have no idea how it's done, and it seems like it'll fit in well with my Zero Carry thinking. So I'm sure I'll check it out eventually. Which means he really has nothing to gain by sending it to me.

As for the marketing blitz: I understand why people would be annoyed by this style of promotion, but I also understand what he's trying to do. He's trying to maximize pre-sales of a digital product that will likely get bootlegged the moment it's released. I can't blame him for that.

And a 15-page thread on the Cafe before something's even out? That's healthy for 2026. Years ago you'd regularly see 30 or 40-page threads for tricks that hadn't been released yet. And sometimes the tricks didn't even really exist. Those were the days.

I've always enjoyed the correspondence I receive from writing this site. It always gives me something to think about and often inspires future posts or things I want to try out in magic.

That being said, it can also be a little overwhelming. It probably averages about 15-20 emails a day, which is not exactly Henry Winkler during peak Happy Days level — [Fonz Gif] — but it's still a lot when the emails are frequently proposing new ideas or asking for an opinion on something. It's not like getting an email from my grandma saying, "Thinking of you!" that I can respond to with a simple, “Love you, Nana!” They're emails that require some thought even just to give a minimal response.

I used to feel somewhat bad about giving short responses to long emails. If someone writes me eight paragraphs and I respond with three sentences, that feels inadequate in some way—even though I know people understand the position I'm in.

Fortunately, Google has created a new feature in Gmail that solves this issue. It now gives you a proposed response that you can just send with one click.

Now, I would never use these responses because they’re frequently nonsensical, and even when they're not, they go beyond cursory to the point of being insulting. But what I appreciate about them is that they make me feel better about my own responses, even if they're just a few sentences. I could have really bitched out on it and had a robot write the whole thing for me.

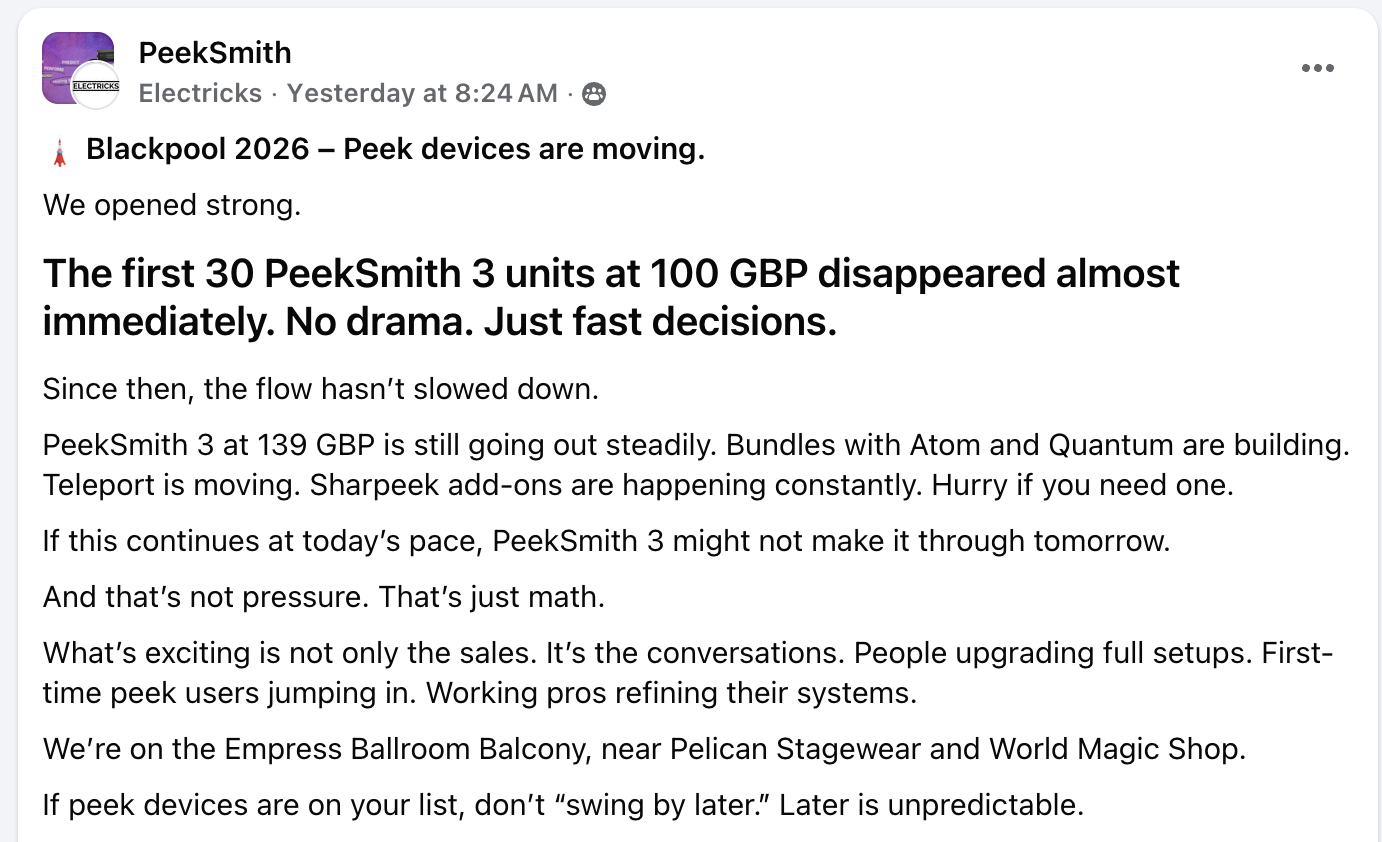

This Week In Bad AI Marketing

Dear Magic Companies:

You can just write a Facebook post from your own fucking brain. You don't have to run everything through ChatGPT and end up with this gobbledygook.

"No drama. Just fast decisions."

What does that mean? Drama? There's no context in which I would ever assume "drama" because you sold 30 units of a magic trick at a place you went to sell magic tricks.

AI has taken a powerful rhetorical tool (antithesis) and reduced it to just: "It's not X. It's Y." And it uses it constantly. But because it's not a human living in the real world, it doesn't really understand the dynamics that make for a meaningful juxtaposition.

The issue is that AI is trained on a lot of marketing, SEO, and "conversion" writing. It's optimized for a persuasive rhythm, and then it just tries to fill in the blanks even if it has to use nonsense. "No drama. Just fast decisions."

Oh, okay.

"What's exciting is not only the sales. It's the conversations."

Oh! Exciting conversations! I wonder what they were? Did someone use their product to land a huge contract? Did a 12-year-old save up his paper route money to buy one? Did someone incorporate a PeekSmith into a trick they did to propose to his girlfriend?

No. The "exciting" conversations were:

"I'm upgrading my setup."

"I'm buying one for the first time."

"I'm refining my systems."

Oooooh… tell me more.

Look, goofballs, that's just three ways of saying "people are buying things."

AI doesn't know these conversations are inherently dull, so it doesn't know not to frame them as exciting.

"If peek devices are on your list, don't 'swing by later.' Later is unpredictable."

Later is unpredictable. Damn, bro… that's real deep.

This is another thing AI does constantly. It attempts a mic drop when it's holding a hairbrush. It wants to be profound, but it's impossible to be profound when the underlying message is: "We might sell out of our peek device." So you get this mismatch between the language and the actual intent, and it ends up sounding dopey.

I'm not just trying to point out every dumb flaw in this post. I'm trying to empower you. You can just write stuff as a human for other humans.

Offloading all your marketing to AI makes you sound generic and corny. And it undermines your ability to capitalize on the most compelling thing you have when promoting a product or your company, which is someone relating their lived experience.

Speaking of PeekSmith. I have one that I will be selling, along with a few other electronic devices (Synaptic, an Anverdi Mental Die, and maybe a couple of other things). All unused, and at least at a 30% discount. This is part of my attempt to move towards a more minimalistic magic collection.

If you’re interested, the information will be sent with the next Keepers magazine. Keep an eye out for it on the 1st and get in touch quick, as the things will go first-come, first-serve. Don’t wait for later because—as a wise man once said—”later is unpredictable.”

Byyeeeee! See you back here in March